A hodgepodge of memories built from various adventures, starting from the patriarch of invention and creativity, my Dad. In his mid to late thirties, he started several businesses, including one that began in our garage. “Would you like to make some money?” That was a question James, Jon, and I heard often. Sometimes, we would pass on an opportunity, knowing it would require what we felt was a lot of work. Other times, one of us would take Dad up on it, getting deep into whatever project he was working on, only to discover that it was much more work than we initially anticipated. And then, occasionally, we’d do the job, earn the reward, and be grateful for both the cash and work.

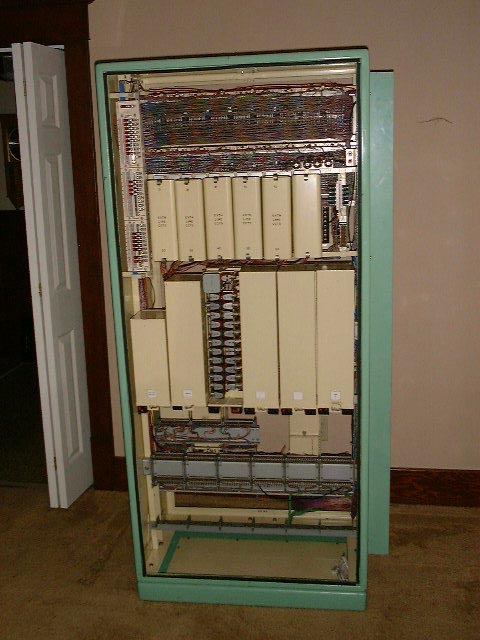

I remember one afternoon we came home from school and watched Dad and two other guys we’d met a handful of times before struggling with a six-foot metal tower frame full of wires. Some of the visible connection points looked like something I had seen before, maybe from a movie or a television show. The last of these towers now stood inside our garage, Dad’s sweat dripping onto the concrete floor. “Who wants to make some money?” he asked all three of us. We stood there.

“Doing what?” James asked.

“What are these?” Jon asked, touching the smooth edge corner of the tower.

“These,” Dad smiled, “are old telephone switch boxes.” Dad pointed to the quarter-inch female ports scattered up and down the tower. “Operators would connect calls through this tower,” his finger pointed from one female connector up to another eight inches away, “patching them through here. What we’re going to do is reclaim all the silver from the switches.”

“How?” James asked. The last time we had a project like this, James refused to have anything to do with it. Sure, he missed out on roughly twenty bucks. That was a lot of money in the mid-80s. But the work sucked. I know because Dad insisted I help with it. After all, I was the oldest. Dad figured I could convince my brothers to help if I got in on it. Jon got on board, but James? He stood his ground.

“Well, we start by ripping everything out of the towers.” Demolition! What kid didn’t like tearing something to shreds? A few years from now, my cousin Doris would ask me to come to Washington to help demolish a bathroom, which was a blast! But the work was hard. I didn’t mind. It was a hundred dollars for ten or eleven hours of work. Not bad when the minimum wage was under three dollars an hour. But that’s not what we were talking about today. Today, we wanted to know what we could make. “Then we tear out every switch and every bit of silver we can salvage. I’ll sell it, and we’ll split whatever it is for everyone who works. Sound like a plan, guys?”

“Heck yeah, Dad! Where do we start?” Jon was ready to rip into it with his bare hands.

“Well, I think you can work down here,” Dad pointed at the lowest point of the tower. “And Joe? You and James, start here,” he pointed at the top, “work your way down to the middle. We need to strip out the tower of all these components, and then we’ll strip the switches and wires. And I’ll show you guys how to do it.”

“Cool!” Jon shouted, racing to grab Dad’s toolbox. It weighed more than he did, but he tried to get it anyway. “Joe? Can you help me?”

“Yep.” I reached down, letting Jon hold it with me, making him feel like he was carrying it. I’m pretty sure he knew he wasn’t doing it, but it worked for him. “Dude! Just let go.” I finally said. Jon almost made me trip twice; all we had to do was go less than five feet from the towers. Sheesh.

“Do I have to help?” James whined.

“Yes. This is a family project.”

“More like a conscripted family project,” James muttered to himself. Snatching a Phillips head screwdriver, he started undoing the parts connected to the tower.

Us kids lasted about an hour, James muttering under his breath every few minutes. Dad had enough of his whining, Jon’s getting in the way of everyone, and me groaning about my hands after we unscrewed what felt like five hundred screws. My fingers throbbed, and my fingers ached. The three of us disconnected most of the first tower without pulling apart the switches or seeing any silver.

This happened right after Dad decided to salvage a bunch of seashells and make something out of them. I remember one day, he came home, and the whole garage smelled like the beach. You know, that smell you can’t quite put your finger on, but it smells like ocean and fish? Yeah. That’s how our garage smelled when we came home from school. Not exactly disgusting, but it was odd.

We had a surplus of 35mm film cans from Dad’s work at Alpha Cine, the film laboratory in Seattle. We had a lot. I never stopped to count how many there were, but we had various sizes. But the ones we had a lot of were fifteen inches in diameter, roughly two thousand feet of film, or twenty minutes of screen time. Repurposing the empty cans, Dad filled the cans with seashells of various shapes and sizes. We had hundreds of different types of shells, all interesting, but not all were from the shores of the United States.

“I’m going to make seashell pictures,” Dad said. The excitement in his voice was similar to a character I idolized in the 1980s, Colonel Hannibal Smith, the cigar-chewing leader of the A-team. I could hear Hannibal’s ‘I love it when a plan comes together’ line from the show in Dad’s tone. The pictures were very creative and lucrative enough to garner the attention of one of the shops on board the Queen Mary in Long Beach, California.

But that’s a story for another day.

Leave a comment